J.G. Ballard - Where to Begin - Top Five

I've compiled a list of five novels, in publication order, to introduce you to the unique and imaginative work of one of Britain's greatest writers.

The future is going to be boring. The suburbanisation of the planet will continue, and the suburbanisation of the soul will follow soon after.

Who doesn’t love a list?

Ballard sure did. From experimental works like The Index, a fictional bibliography for a book whose content is presumed lost or suppressed, or What I Believe, part prose-poem, and part sincere, part hyperbolic manifesto of sorts, his admiration of The Warren Commission Report—absolutely amazing stuff!—and Crash Injuries, the medical textbook he once referred to as his ‘Bible’, or how about Ballard’s curious appearance on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs, promoting The Kindness of Women, where, among his selections, “The Teddy Bears’ Picnic” features; Ballard saw the literary potential of lists to enumerate both meaning and bewilderment, often simultaneously.

The internet is littered with lists on everything from The 10 Best Fibre Broadband Suppliers to 25 Real-Life Ghost Stories That Will Terrify You, and equally loved by insomniac scrollers and search engine algorithms alike. Lists can offer a little footing for the uninformed, and for those already fluent in their subject, who may have compiled a mental tally of their own, they provide an opportunity to compare, to discuss, or lambast.

And so begins this new series: Top Five.

With this list, I’ve chosen to focus on the novels of J.G. Ballard, one of my all-time favourite writers. I have selected five that I feel are emblematic of his career. One to five is not a ranking but chronological. It also makes for a decent reading order.

The list:

The Drowned World

The Atrocity Exhibition

Crash

The Unlimited Dream Company

Super-Cannes

Explained:

1. The Drowned World (1962)

Where better to begin than with Ballard’s first novel (or at least what he refers to as his first real novel, having blocked reprints of 62’s The Wind from Nowhere).

Synopsis

The polar icecaps have melted; seas and temperatures have risen. Most of the Earth is now uninhabitable. The few surviving humans are forced to the North and South poles, which have become tropical, redolent of the Triassic era. There, Dr. Kerans and the others must contend with not only the futility of their surroundings but also the threat of sociopathic pirates.

The Drowned World has remained popular for its bleak and prescient depiction of global warming devastating the Earth. But as with all Ballard novels, it is neither censorious nor a cautionary tale. The unsolvable and worsening situation drives the narrative. Ballard is not so much concerned with cause as he is with effects. His characters are known to embrace catastrophe, to seek the path of their ruination and head towards it.

Ballard followed up The Drowned World with its inverse, The Drought (1964), and later capped off his trilogy (or quartet, if counting The Wind from Nowhere) of natural-disaster novels with The Crystal World (1966).

2. The Atrocity Exhibition (1970)

Ballard’s next novel would not only break from the formula of his previous three but also strip away the conventions of the “novel” altogether. The Atrocity Exhibition is a Morbius strip of non-linear fragments. It is fractured, detached and routinely unsettling in its clinical exploration of aberrant behaviours.

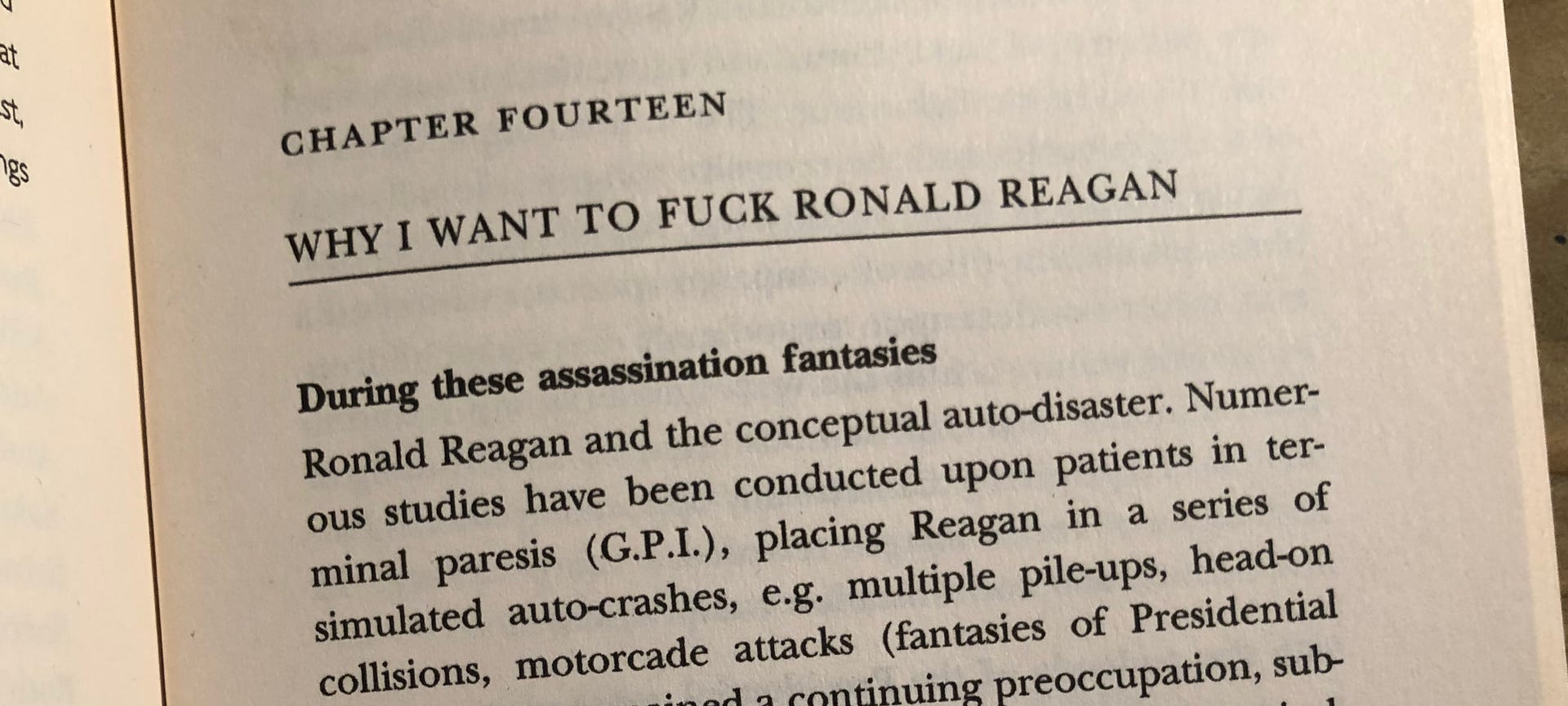

A notorious book, infamously pulped by American publisher, Doubleday, when their CEO saw one of its chapters was titled: Why I want to fuck Ronald Reagan. (Grove Press—a print house synonymous with boundary-pushing literature—later released it in the US.)

The pivot was rather astounding. But as with the rest of Ballard’s work, its genesis can be pinpointed. In 1964, while holidaying with his family in San Juan, Mary, his wife and mother of his three children, became seriously ill with an infection that led to severe pneumonia. Three days later, she died.

My direction as a writer changed after Mary’s death, and many readers thought that I became far darker. But I like to think I was much more radical, in a desperate attempt to prove that black was white, that two and two made five in the moral arithmetic of the 1960s. I was trying to construct an imaginative logic that made sense of Mary’s death and would prove that the assassination of President Kennedy and the countless deaths of the Second World War had been worthwhile or even meaningful in some as yet undiscovered way.

- From Miracles of Life

Rather than attempt a synopsis here for The Atrocity Exhibition, it is perhaps more instructive to list further examples of its chapters:

[2] The University of Death, [4] You: Coma: Marilyn Monroe, [8] Tolerances of the Human Face, [12] Crash!, [15] The Assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy Considered as a Downhill Motor Race, [Appendix] Princess Margaret’s Face Lift.

3. Crash (1973)

Vaughan died yesterday in his last car-crash. During our friendship he had rehearsed his death in many crashes, but this was his only true accident.

The origins of Crash, by which I mean the sexual metaphor Ballard conjured between colliding automobiles and their drivers, began in The Atrocity Exhibition. But whereas the chapter titled Crash! exists as an introduction to this theory, Crash, the novel, is Ballard’s dissertation.

Synopsis

James Ballard—yes, he used his own name—driving home, loses control of his car, where it skids into oncoming traffic and smashes head-on into another vehicle, carrying a young woman doctor, and her husband, who is catapulted through the windscreen, killing him instantly. While James and the doctor, Helen Remington, are barely injured, the ordeal imprints itself in their psyche. The two begin an affair, consummated exclusively in cars. Soon, they meet a contingent of variously impaired crash victims who share their newfound fetish, led by Robert Vaughan, a man who catalogues photographs of road accidents and stages recreations of infamous celebrity car crashes, and whose ultimate fantasy is to die in such a wreck, taking the life of actress Elizabeth Taylor in the process.

Crash is an audacious book. Of all his works, Ballard called it the most important. Martin Amis, reviewing Crash in ‘73, seemed perplexed by the material and the author’s new direction, at one point writing What is Ballard getting at? In later years, Amis came around, saying It took me a long time to get the hang of Crash, and while reviewing David Cronenberg’s 1996 film adaptation, wrote:

The novel is indifferent to the passage of time and has lost nothing in twenty-five years. It is like a clinical case of chronic shock, confusedly welcomed by the sufferer.

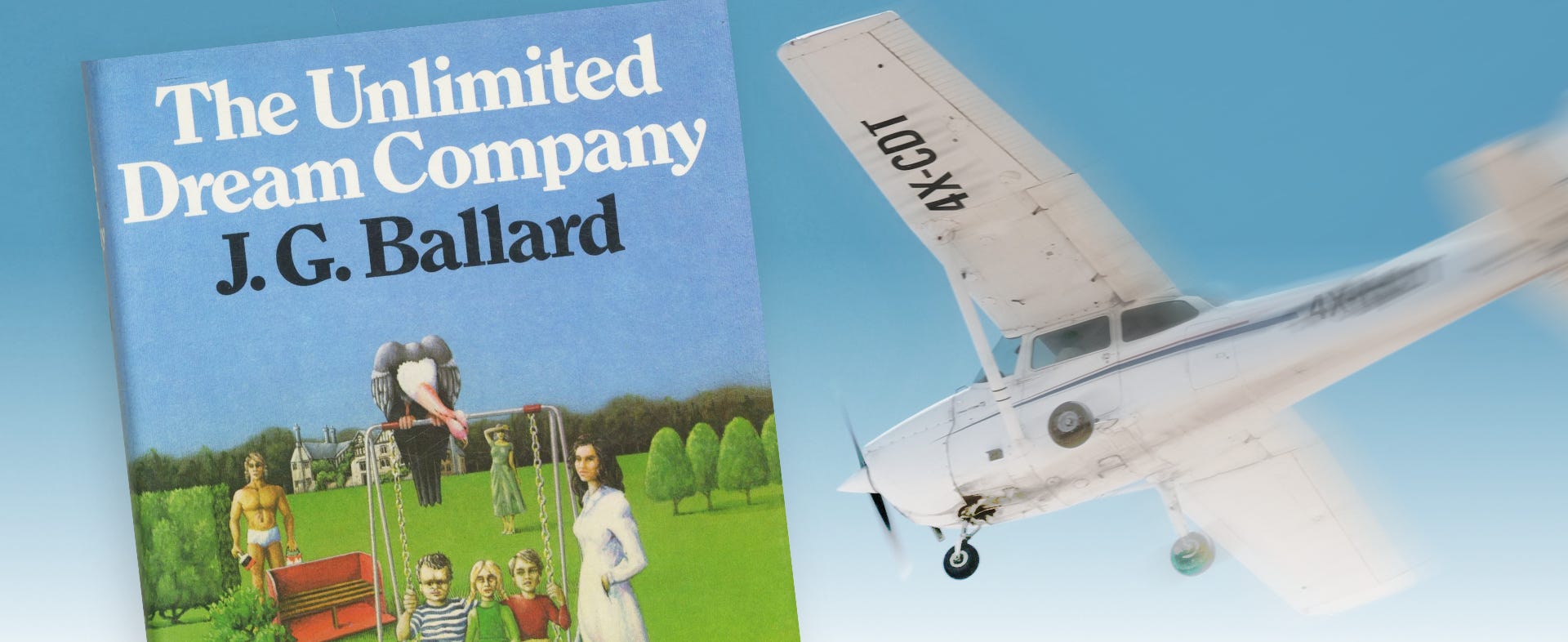

4. The Unlimited Dream Company (1979)

For readers already well-versed in Ballard's fictional hinterland, The Unlimited Dream Company might be the most curious and remote of these five novels I have selected.

Anthony Burgess would agree with its inclusion, however. He once wrote This is perhaps the best novel that Ballard has written, in Ninety-Nine Novels (OOP, but now a podcast), a selection of his favourite English-language novels published between 1939 and 1984.

Synopsis

A young man named Blake steals a plane and, ten minutes after he is airborne, it erupts in flame and crashes into the Thames. Water quickly fills the sinking aircraft as he struggles to release himself from his harnesses. He escapes—or so we’re told—and finds himself in Shepperton, a quiet suburb outside of London notable for its film studios. Blake, having miraculously survived, soon discovers he has supernatural powers. He also cannot leave. The townspeople regard Blake as a kind of God, whom they follow as he transforms their town with spectacular flora and fauna, and fuses with them through impetuous acts of sexual congress.

Blake is an unreliable narrator, so we don’t definitively know if the book's events are real or if they’re visions from the afterlife of our actually drowned protagonist. But due to the explicit scenes in the novel, erring on the side of it being imagined (or at the very least, warped) will be the most palatable for the majority of readers.

It is undoubtedly Ballard’s most surreal novel. And while as an author, Ballard was known to write three or more books around a similar theme, The Unlimited Dream Company stands alone in his bibliography.

Aside: I also find it rather funny that Ballard, who himself lived in Shepperton, wrote this demented tale of a man with supernatural abilities around the time the nearby film studios were shooting interior scenes for the Christopher Reeve Superman movie.

5. Super-Cannes (2000)

Synopsis

Eden-Olympia, the ultra-modern ultra-exclusive business park for society’s elite situated in the hills atop Cannes, has just received two new residents. Paul Sinclair quit his job to follow his wife, Dr. Jane Sinclair, who was offered a six-month secondment there after her once-amiable predecessor went on a killing spree with an assault rifle before taking his own life. While his wife begins her practice, Paul Sinclair, flush with free time, attempts to uncover the reasoning behind the shocking massacre and why Eden-Olympia may not be the paradise it first appears.

Much in the same way that Ballard’s first four novels shared thematic similarities, so did his final four: Cocaine Nights (1996), Super-Cannes (2000), Millennium People (2003) and Kingdom Come (2006), which all deal with, namely, suburbanite and/or yuppie unrest among small townships and gated communities.

Super-Cannes bears an especial likeness to the novel that preceded it, Cocaine Nights, swapping the sun-scorched Spanish enclave of Estrella de Mar for the uber high-tech Eden-Olympia. But, while it is longer (I believe it’s actually Ballard’s longest novel), Super-Cannes is somehow inexplicably tighter, more engaging; the premise was, in this reader’s opinion, perfected on the second go round.

Wait, no Empire of the Sun?

Empire of the Sun is Ballard’s best-known book. It is, if you didn’t know, an autobiographical novel based on his boyhood experiences in Shanghai, interned at a Japanese prisoner of war camp during WWII. Steven Spielberg adapted it for the “big screen” in ‘87, starring a young Christian Bale as “Jim”.

It’s a remarkable book. Certainly, read it—do. Its absence from this list is not due to any lack of merit or to dismiss the book that most people have heard of. I simply believe it, its sequel, The Kindness of Women, and Ballard’s marvellous autobiography, Miracles of Life, are best read later.

Many themes and recurring images throughout Ballard’s work can be traced back to his youth, what he saw and experienced. These sights knitted into the grey matter of his fertile mind, which later gave birth to elaborate, distorted allegories of catastrophe and characters with an emotionless—almost workmanlike—attitude to violence.

Empire of the Sun isn’t a typical Ballard novel, but it is indicative of what came before and after its writing.

Closing

And with that, I am curious about you, reader. Where is it you fall on the Ballardian continuum? Have you read none, some or all of his work? Do you favour a certain period or format, say his short stories or non-fiction, or even perhaps his avant-garde advertisements during his tenure at Ambit, over his novels? What is your favourite, or favourites? And, if you have a top five list of your own, do share it below. I’m interested to see how yours differs from mine and why.