Who reads Norman Mailer anymore?

The Executioner’s Song: A sort of review but not really of a sort of novel but not really

. . . The answer, I suspect, is very few.

Certainly, Mailer’s cultural notability (or notoriety, depending on your stance on the man) has diminished since he was alive, alternately releasing books of prodigious size and sparring both words and fists with his peers, along with the occasional headbutt, for good measure.

But why? What makes a figure like Mailer, once often touted as America’s greatest writer, fade into the annals of literary oblivion? Was he never that talented to begin with?1 Was the acclaim his books earned at the time justly warranted or inflated by celebrity and scandal? Or was it in truth the exhibitionism—between half-sloshed television appearances, his many public spats and feuds, a failed mayoral candidacy in New York, a lacklustre foray into film, and not to mention the hideous knife-assault in 1960 he levied at his then-wife—that totalled too much baggage to take Mailer-the-writer seriously and caused his eminence to wither?

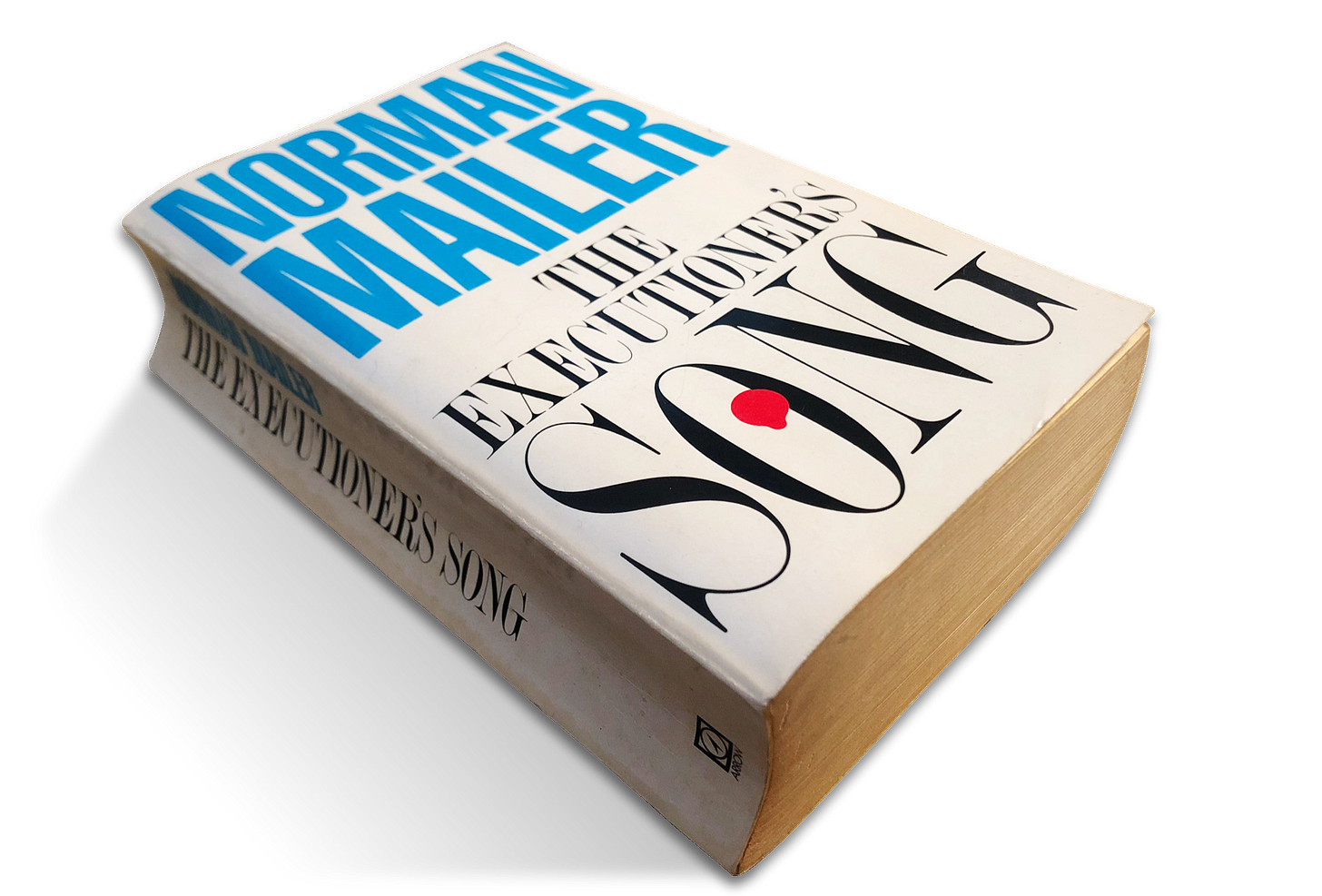

Believing the reasons likely manifold, I went on the lookout among the shelves of second-hand bookstores for a not-too-battered copy of this author’s 1980 Pulitzer-winning work.

It took a while—a couple of years in fact—to chance upon one in the wild. Scouring the “M”s, I’d occasionally spot copies of The Naked and the Dead, but, alas, it was not the book of his I was after2.

An appetite to read The Executioner’s Song arose in me not long after finishing Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, another—decidedly more famous—account of a baffling murder spree and the capture, sentencing and death row proceedings for its assailants.

I’d first learned about it, and Mailer more broadly, in Martin Amis’s The War Against Cliché and The Moronic Inferno, two incisive essay collections whose pages are filled with the appraisals of many literary giants, still luminous-as-ever and other’s who, for whatever reason, no longer shine so brightly.

In Cold Blood and The Executioner’s Song share many commonalities. Additionally, both . . .

Were written by established fiction authors with larger-than-life public personas.

Were labelled “non-fiction novels”.

Are considered by many to be each author’s best work.

Had film adaptations. I.C.B. in 1967, T.E.S. in 1982, and share a Rotten Tomatoes Fresh rating of 75% and 74%, respectively (at the time of this writing).

But while The Executioner’s Song won the Pulitzer—a lustrious prize Capote’s book failed to secure—it hasn’t seen the staying power of In Cold Blood, which now has been elevated to the status of modern classic.

In Cold Blood’s veracity was also heavily debated after its publication. Many questioned how faithful Capote was to his book’s subtitle, “A True Account of a Multiple Murder and its Consequences”, and how much it was reshaped and even fabricated by the savvy storyteller.

Take a look at this excerpt, for example:

Among Garden City’s animals are two grey tomcats who are always together – thin, dirty strays with strange and clever habits. The chief ceremony of their day is performed at twilight. First they trot the length of Main Street, stopping to scrutinise the engine grilles of parked automobiles, particularly those stationed in front of the two hotels, the Windsor and Warren, for these cars, usually the property of travellers from afar, often yield what the bony, methodical creatures are hunting: slaughtered birds – crows, chickadees, and sparrows foolhardy enough to have flown into the path of oncoming motorists. Using their paws as though they were surgical instruments, the cats extract from the grilles every feathery particle. Having cruised Main Street, they invariably turn the corner at Main and Grant, then lope along towards Courthouse Square, another of their hunting grounds - and a highly promising one on the afternoon of Wednesday 6 January, for the area swarmed with Finney County vehicles that had brought to town part of the crowd populating the square.

Within this passage, the only pertinent information is that a large crowd is formed at Courthouse Square—the crowd, we later find to be a furore of journalists, photographers, television reporters and cameramen, awaiting the arrival of Hickock and Smith, the murdering duo at the book’s centre.

The two tomcats are an obvious invention and entirely superfluous. They serve as a little whimsical blocking (to use a film term). By following these small, industrious creatures as they go about their daily rituals, the mass of activity at Courthouse Square, they—and we in turn—encounter, appears all the more monumental from the diminutive standpoint it's observed. Capote clearly also seeks to draw an analogy between the lives of the tomcats and Hickock and Smith, two other “dirty strays”—and two other opportunists who prey on the defenceless.

In Cold Blood, throughout, is perfumed with Capote’s insights. The narrative is mediated through a singular viewpoint (his own). He explains, he embellishes, he offers potential answers. Its prose is that of a conventional novel, and because of it, the line between fact and fiction, at times, blurs.

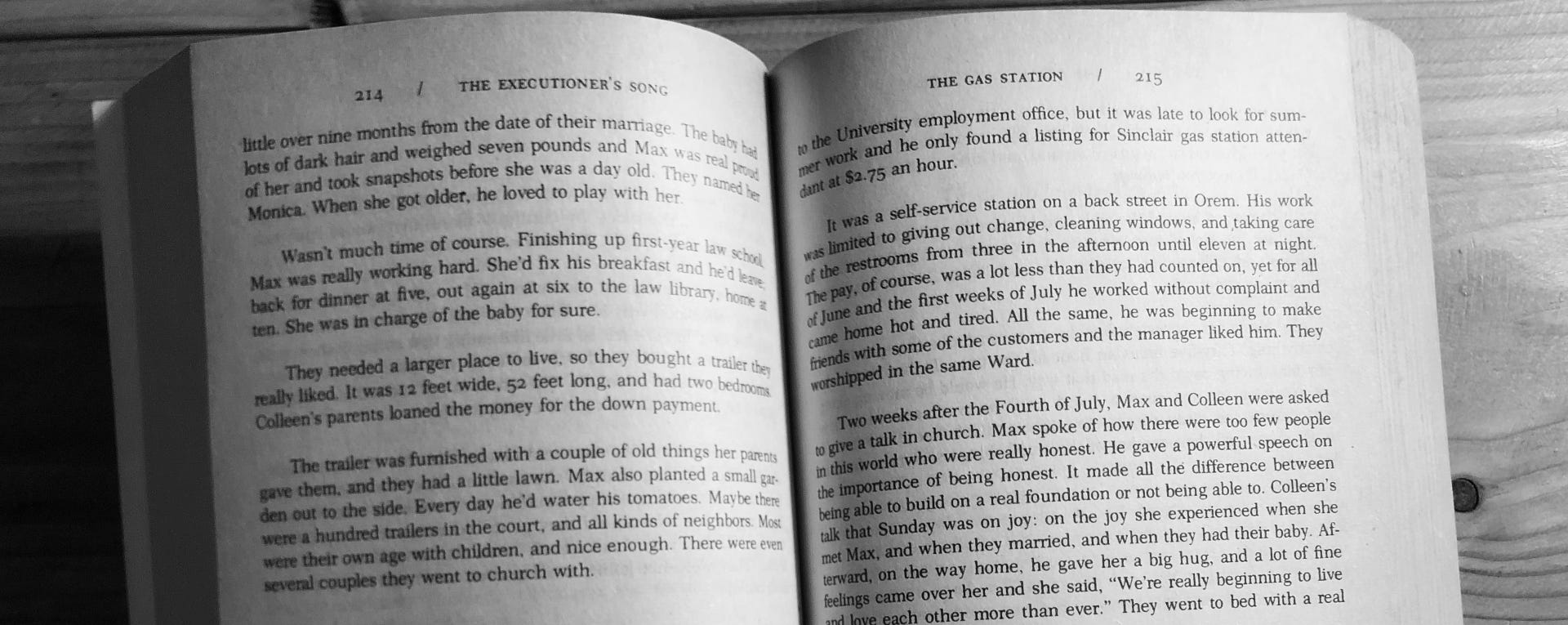

By contrast, here is an excerpt from The Executioner’s Song:

Next morning, Gilmore was brought from Provo to Orem, and Neilsen saw him in his office, and apologised about the crowd outside. There were TV lights and a lot of reporters and city employees in the hall, but what really embarrassed Nielsen was that half the police force including off-duty officers had also come out. People were even standing on chairs to get a look.

Mailer employs a more direct approach. His book’s prose is spare, almost utilitarian, and for the sheer amount of ground it covers, it needs to be. To Mailer, artful flourishes in language or extemporised pastorals were unnecessary to keep the reader rapt through the lengthy prospect of reading it. Facts alone were enough.

The book is engorged with testimony, transcripts, letters. Multiple viewpoints are afforded space to be heard. Because of this, it makes for a much different experience from In Cold Blood. As readers, we are not presented with a central thesis to follow but instead a panoply of material in which we must derive our own conclusions. Or not; the swathe of contradictory views, including those surrounding the death penalty, owing to the idea that wicked acts such as this are messy, chaotic, intrinsically (and lamentably) as much human as inhuman and perhaps not reducible to neat single-thread summations. Certain issues forever evade universal accord.

Going into The Executioner’s Song, I knew nothing about Gary Gilmore, the crimes he was accused of, and what punishment would transpire. Of course, given the book’s title, I’d assumed the nature of his crimes to be murder, but as to specific details—the victim(s), the motive(s), if Gilmore was indeed the rightful culprit, and whether he would see the chair, rope, rifle, injection or would eventually be acquitted—not a clue.

I was impressed by the book and by Mailer’s ability to sustain this complex, multifaceted story through a thousand-plus pages, never once succumbing to the urge to hypothesise. It’s a surprisingly quick read, too, full of lean, spaced-out paragraphs. The longest sections are often transcripts of Gilmore’s letters to his fiancée and others on the outside, which provide the closest, albeit still murky, insight into the way his mind operates.

Is it a novel, however? While in the tradition of In Cold Blood, the absence of its author’s own perceptions and the strict adherence to witness testimony made me struggle to designate it as such throughout this review-of-sorts. (Though, I hope I’ve been clear that I think it’s, in this instance, better for it.) Novel or not, it’s a book, and a book I feel is worth reading, particularly if you admired In Cold Blood, you’re able to find a copy and are not daunted by the prospect of lugging it around with you.

And with that, similar to the book’s revelations, my verdict on Mailer—and any conclusions as to why his work has not endured like some of his contemporaries, including Capote—remain, I suppose, inconclusive.

Perhaps The Executioner’s Song is the one shining exception in Norman Mailer’s otherwise skippable oeuvre; perhaps his other works are all crippled with outmoded ideas, which no longer vibe with today’s hapnin youth and their, like, values, maaaaaaaan!; perhaps I got it all wrong and Mailer’s still well-regarded, widely read and just as relevant as he ever was in the States and my antennae are attuned to his perception—or lackthereof—here in the UK, much in the same way most of us here couldn’t name a single NFL player (I can name only Dan Marino, and only because he appeared in Ace Ventura: Pet Detective); perhaps I ought to read another of Mailer’s books, just to be sure; perhaps; perhaps.

This is one charge I’ve heard from another writer. It perhaps even kick-started the whole desire to read a book by Mailer and see for myself.

Of course, I could have hastened this process by buying online. But even in paperback, The Executioner’s Song is a hefty 1,050-page brick, understandably costly to ship. I was in no rush. There are always plenty of books to read. I eventually paid £3.50 for my copy (pictured). Bargain.